2020 The State of Japanese Tech in the Post-Covid Era

TRENDS2020 has proven to be a thoroughly eventful year for major economies around the world. Within the first two quarters, we have witnessed the unfolding of a global pandemic across emerging and developed markets alike, causing the annual outlook for real GDP growth to trend downwards across the board. While this abrupt and widespread crisis has undeniably caused a short-term recession, it has provided a rare window of opportunity to transform legacy practices; as a catalyst acting upon existing technological tailwinds, this year has seen a rise in newer attitudes towards digital adoption, granting a glimpse into the nascent future of human interaction and workplace productivity.

Japan is no exception. As the world’s 3rd largest economy, with Tokyo being the most densely populated metropolitan capital globally, Japan has seen its share of fascinating trends emerging in the advent of Covid-19. As we step back to evaluate the macro landscape, how exactly has Japan been faring in terms of technology adoption and the startup ecosystem? At UBV, we have identified 3 key trends that strongly indicate sustained growth in SaaS startups in Japan, in terms of 1) Growing SaaS adoption in enterprises, 2) catalyzed government-led digital transformation, and 3) maturing capital markets for the startup ecosystem.

Key Trend 1: Growing SaaS Adoption in Enterprises

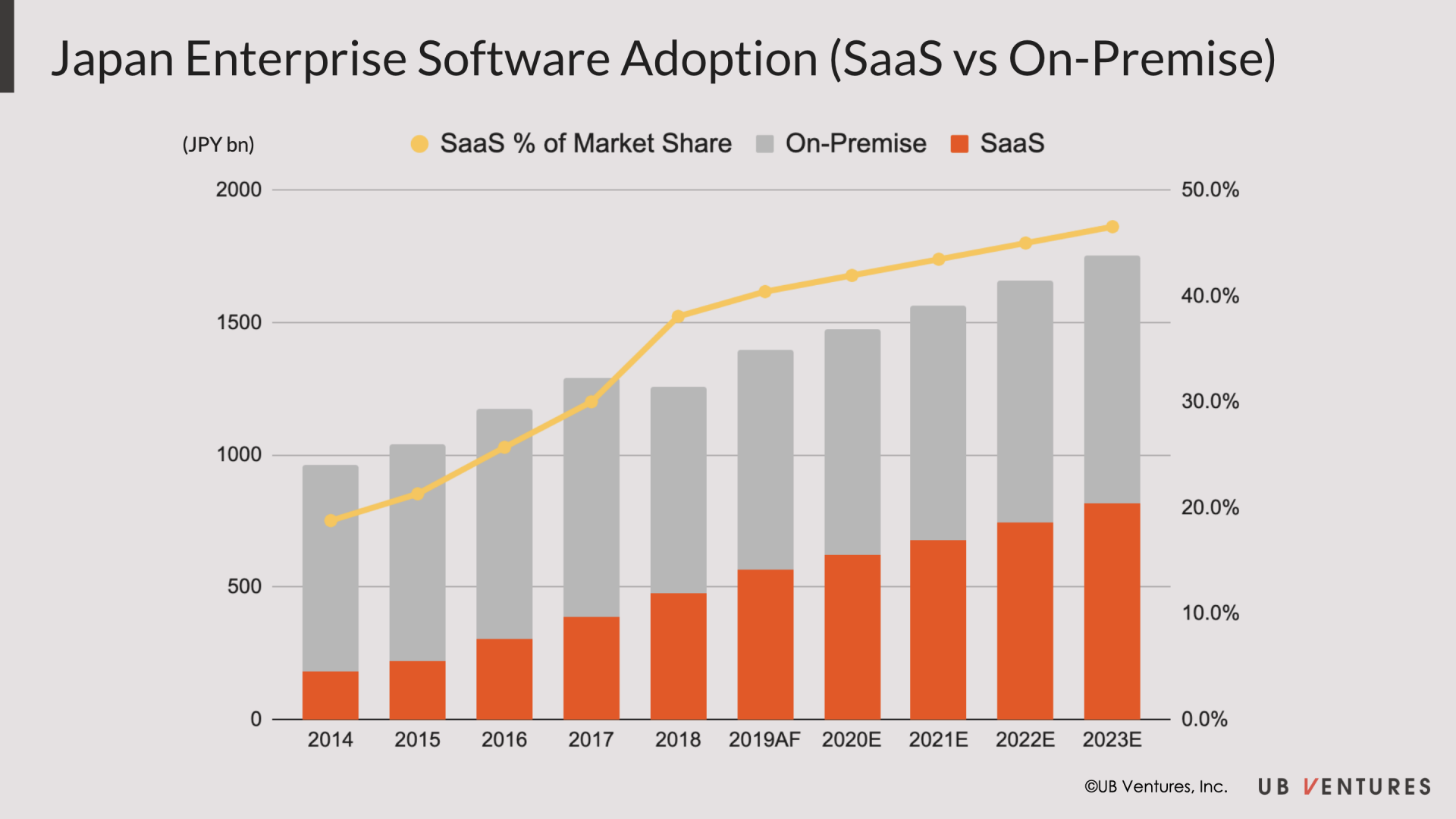

Japan has, for the past decade, already been experiencing a steady increase not only in enterprises adopting software services, but specifically, in SaaS over on-premise services. According to Fuji-Chimera, a Japanese technology consultancy1, from 2014-2019, the overall enterprise software market has grown from JPY 963bn to JPY 1,396bn, or 7.7% CAGR, and is projected to still continue growing to JPY 1,755bn by 2023.

Within this enterprise software market share, we see two main categories respectively: on-premise software (where software is installed on the client-side and generally runs within the enterprises’ local premise itself), and SaaS (where software is hosted on the cloud by the vendor and generally runs within the browser). As enterprises begin to employ more cloud-based services for seamless data access and storage, we have been seeing slowing growth in on-premise software, and conversely, rising growth in SaaS; in the same period from 2014-2019, we saw SaaS grew at 25.5% CAGR, compared to only 1.3% CAGR by on-premise software. Furthermore, SaaS as a % of total market share has similarly increased from 18.8% to 40.4%, indicating that more enterprises are shifting away from the legacy on-premise infrastructure, and migrating their data to the cloud through SaaS adoption. This is projected to steadily increase further to 46.6% by 2023, indicating that SaaS adoption is proving to be a long-term trend, as SaaS offerings continue to mature, leading to lower barriers to entry for data migration to the cloud.

Key Trend 2: Catalyzed Government-led Digital Transformation

In addition to the aforementioned strong technological tailwinds inherent in SaaS usage within the private sector, we now see how in 2020, Covid-19, as well as a timely political transition, has catalyzed the urgency of digital transformation on the public sector as well. Amidst the recent power transition from PM Abe to PM Suga due to the former’s health reasons, PM Suga has promised to push ahead with administrative reforms “to shatter bureaucratic sectionalism, vested interests and bad precedents”2. This pragmatic approach has already seen early signs of change in governmental attitudes towards digitalization. In his inauguration, PM Suga has promised to create a new agency for the decentralization and the digitalization of administrative work, to be led by Digital Transformation Minister Takuya Hirai by end-2020 – clearly, the pandemic has demonstrated the need for the government to use digital technology more efficiently. Even within the financial markets, the Bank of Japan3holds similar sentiments, suggesting that TFP (total factor productivity) growth rate would even show “moderate increase due to adaptation to a “new lifestyle,” advances in digital transformation, and a result improvement in efficiency of resource allocation” as the pandemic would have brought about “a structural change in people’s working styles and firms’ business processes that does not follow the past trend”.

In the same vein, we are also now witnessing a strong push for the removal of hanko (inked seals) and fax usage, led by the new Administrative Reform Minister Taro Kono. This aggressive effort for reform towards a digitally-efficient bureaucracy has gained traction across governmental bodies, with the Environment Minister Shinjiro Koizumi also already axing hanko requirements for several paperwork in solidarity to “swiftly abolishing them”4. While the crisis of this pandemic has undoubtedly tested the robustness of our financial and social infrastructure, it has also provided fresh momentum for the government to critically address legacy issues in dire need of political reform, giving rise to a new era of open-mindedness towards innovative practices, a relentless effort to be pushed forward in tandem with the tech ecosystem in Japan.

Key Trend 3: Maturing Capital Markets for the Startup Ecosystem

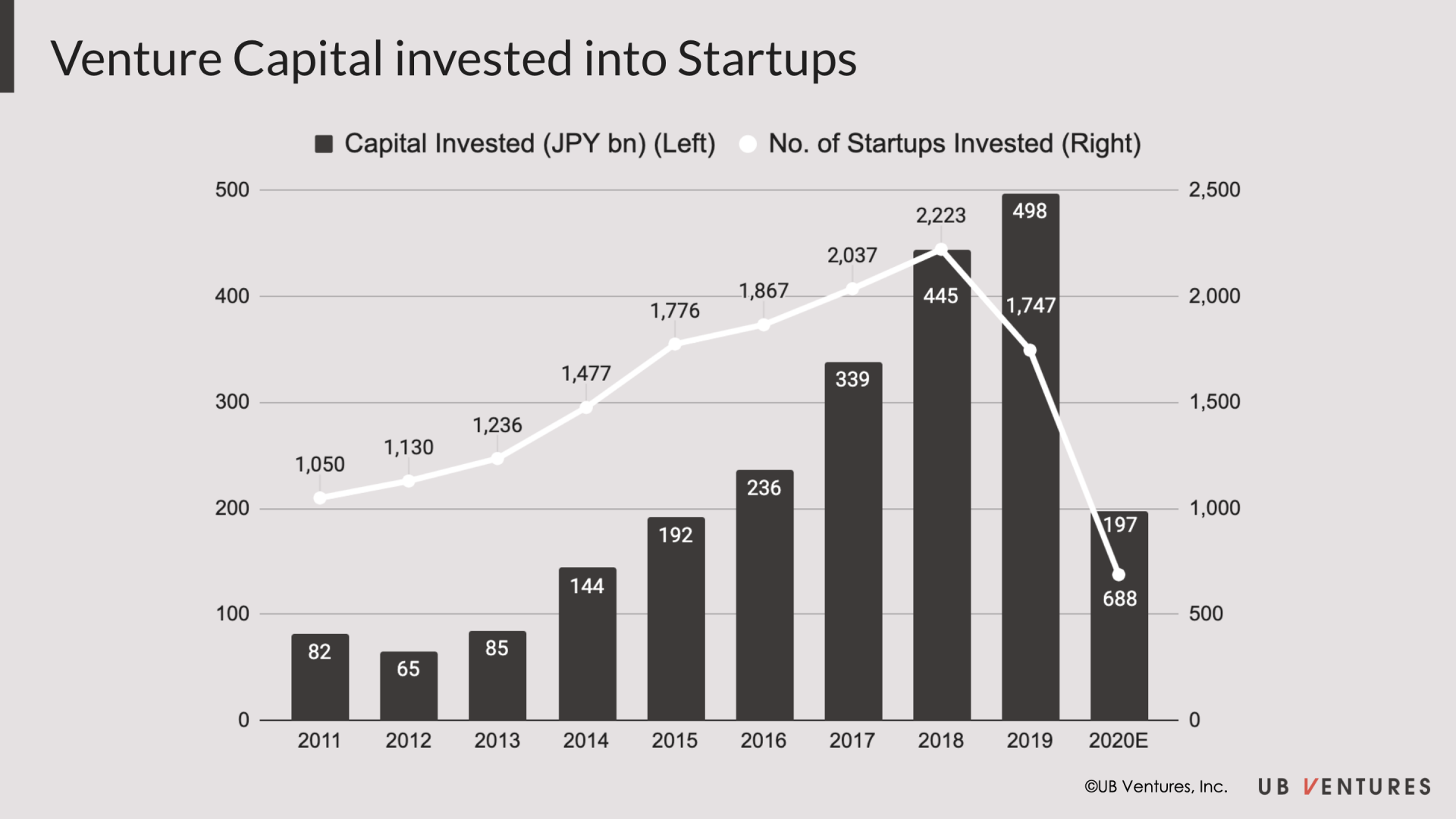

Even on the ground, we have seen Japan’s startup ecosystem steadily growing over the past decade, only recently being put under the spotlight in line with the enterprise’s cloud migration through SaaS offerings, and especially, with the new government’s efforts toward digital transformation. Catalyzed by the pandemic, we have also witnessed accelerated structural changes in the remote work practices adopted by SMEs and large traditional Japanese conglomerates alike. Since 2012, we have identified some key VC trends enduring in Japan5, sustaining even amidst Covid-19. There has been a steady mean increase in venture capital deployed into startups, at 29.4% CAGR to JPY 500bn in 2019. Similarly, there has been an increase in the number of startups that have fundraised at 7.5% CAGR, albeit with a noticeable drop in 2019, to 1.7k startups in 2019.

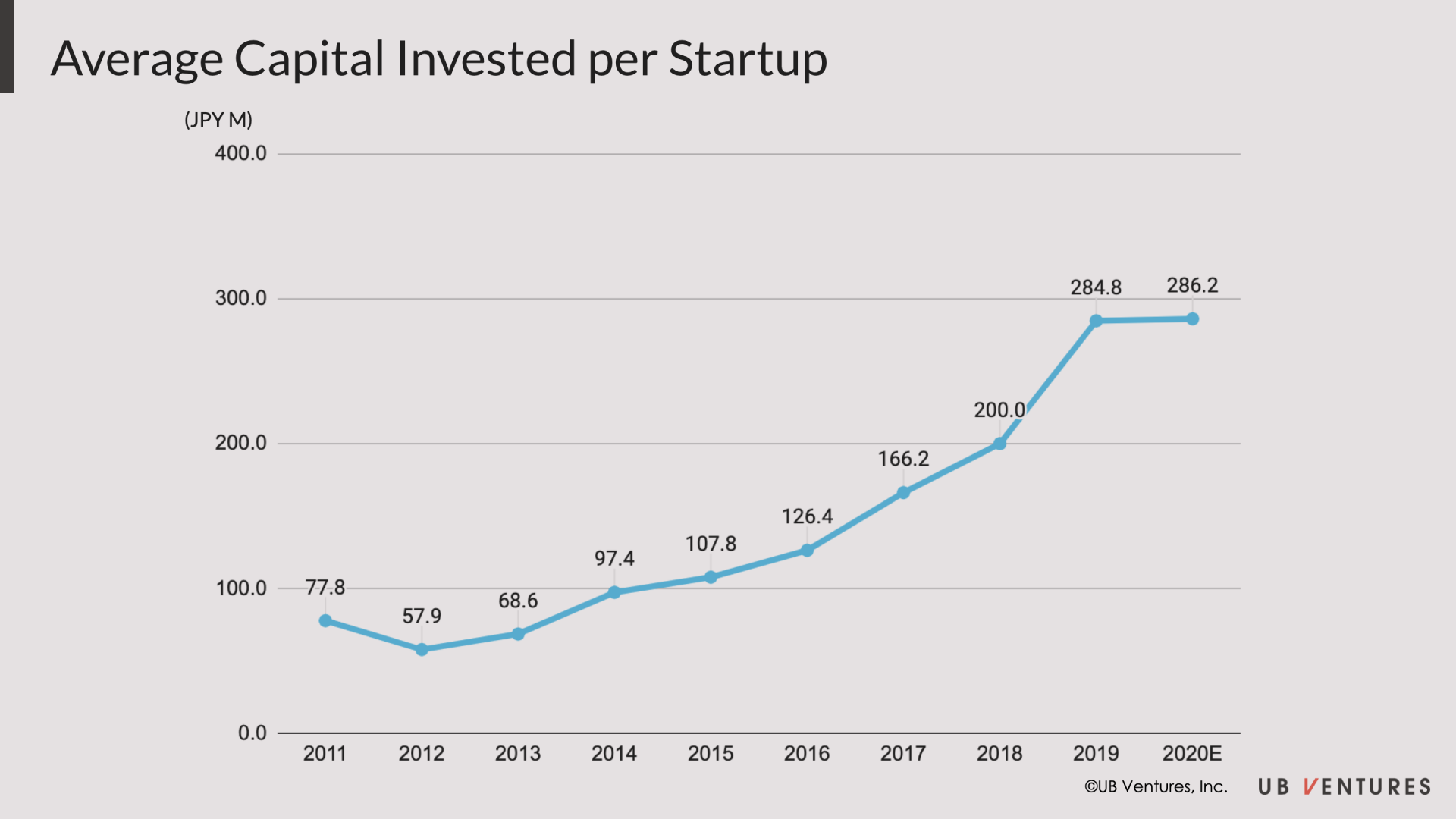

As a result, on a simple average basis, the amount of capital deployed per startup has been steadily increasing, with a 20.4% CAGR to JPY 284.8m per startup in 2019. From the 2020 H1 available data, we can deduce that even though venture capital deployed into startups and number of startups fundraising have fallen to below half of 2019 figures, the net amount of capital deployed per startup in 2020 so far has still been rising, from JPY 284.8m per startup in 2019 to JPY 286.2m per startup in 2020 H1. Overall, even though Covid-19 would have affected the gross amount of venture capital deployed as well as the number of startups fundraising, the growth in net amount of venture capital deployed per startup has proved to stay relatively robust, all while the pandemic unfolds. What does this trend mean for the Japanese startup ecosystem? On a mid-to-long term basis, a steadily increasing average amount of venture capital deployed per startup, on a cursory level, is symptomatic of a maturing startup ecosystem, whereby a startup is willing and able to stay private and raise larger rounds after Series A funding.

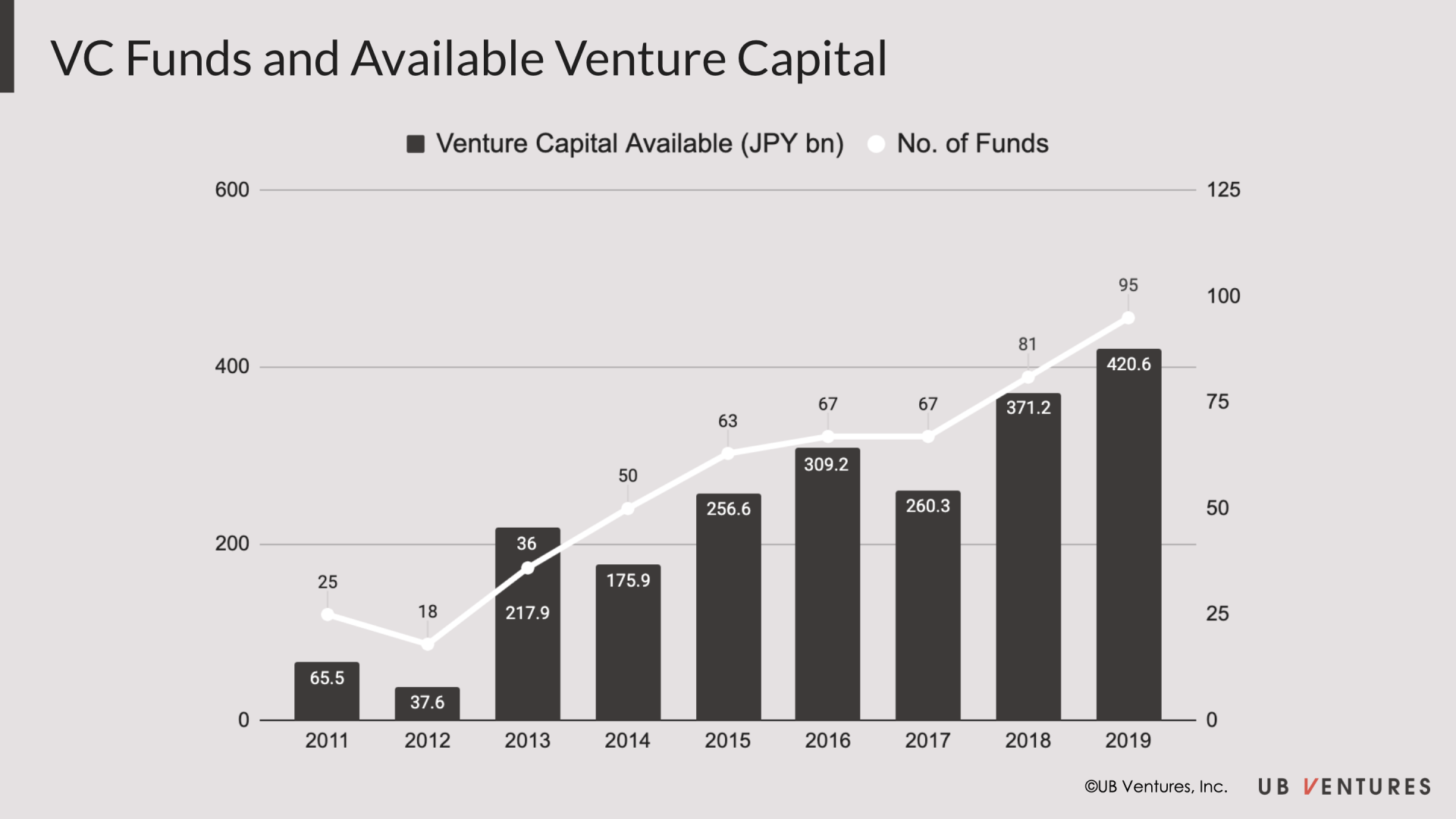

This can be explained by supply-demand factors in the ecosystem’s capital markets: on the supply-side, we have seen an increase not only in the gross amount of venture capital available, but more fundamentally in the number of VC funds being set up, thereby accommodating a myriad of investment strategies, catering to a wider catchment of potential startups both domestically and abroad. In many ways, this phenomenon has been made possible by deeper and more extensive LP involvement, via active trust-building efforts between GPs and Japanese conglomerates, manufacturers, and financial institutions both in Tokyo and in the countryside, all increasingly looking for strategic exposure to emergent innovation trends, as well as financial opportunities to achieve more favorable returns than from their current investing activities.

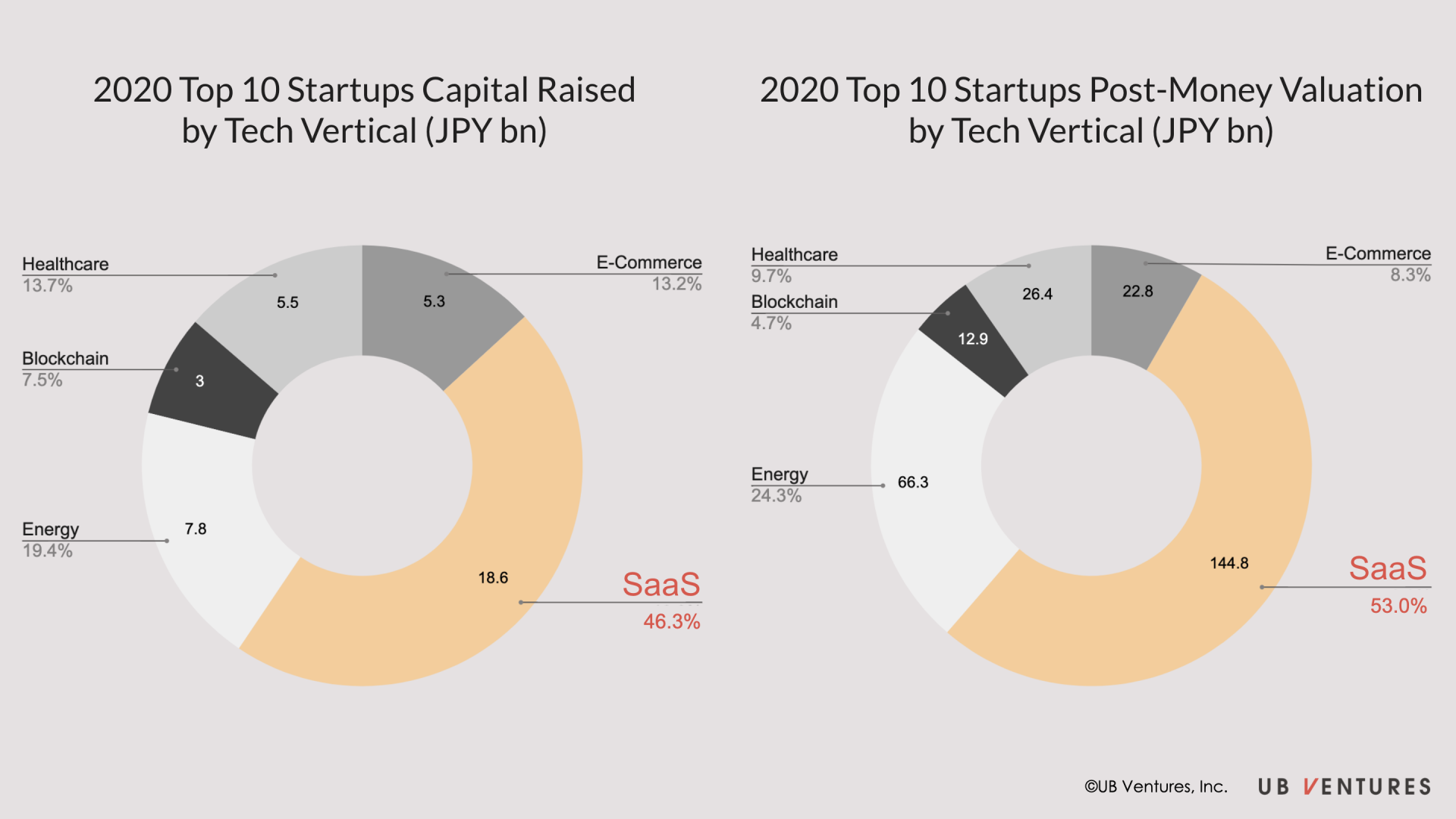

On the demand-side, we have also witnessed not only an increase in the number of startups fundraising, but also the quality behind the startups that have successfully up-rounded beyond Series A, thereby being able to raise far greater amounts of venture capital. In particular, of all tech verticals, SaaS startups have been able to raise the most capital6. In 2020H1 alone, 4 of the top 10 startups with the highest raised capital have been SaaS startups, totaling JPY 18.5bn or 46% of the top 10 aggregate raised capital, and in total fetching the highest valuations, totaling JPY 144.8bn or 53% of the top 10 aggregated post-money valuations. It is worth noting that these high amounts of capital raised by SaaS startups have even exceeded those in energy and healthcare categories, sectors that traditionally require extremely high R&D and capex to keep growing.

Overall, all of these key trends with regard to the capital infrastructure ready and available points to a steadily maturing startup ecosystem in Japan, with increasing interest and investment sentiment from capital providers being allocated to foster and sustain the growth of software-related startups in the mid-to-long term, a key driving to further accelerate digital adoption across Japan as a whole.

Predictions on SaaS Trends for Japan in the Post-Covid Era

In light of the 3 key trends of growing SaaS adoption in enterprises, catalyzed government-led digital transformation, and maturing capital markets for the startup ecosystem, this historical juncture looks to present a new set of unique opportunities for Japan’s technological progress ahead. Here at UBV, we lay out 3 high-level predictions for the Japan ecosystem in the post-Covid era.

Firstly, SaaS productivity tools for enterprises, specifically, have become and will continue to grow in Japan. To enable seamless communication amongst online/offline workplace cultures, even Japanese conglomerates recognize the need to implement the necessary means to facilitate this communication for a new normal where remote work is a permanent fixture. According to a survey conducted by the Japan Business Federation in April 2020 at the heart of the pandemic, 97.8% of its 406 member firms responded that they had instituted teleworking measures. This has served to force traditional Japanese corporates to adopt digital services to accommodate telework arrangements. For instance, one of NEC’s group companies has begun to use DocuSign’s cloud-based e-signature service to enable paperless transactions to be completed7. Across the board, many companies have out of necessity, also taken the step to begin using other common SaaS productivity tools such as Zoom, Slack/Teams, which are likely to become permanent practices as individuals realize not only the convenience during telework, but also the inherent inefficiencies they ultimately solve.

Secondly, remote work arrangements will be a permanent fixture in Japan, although its extent will vary by corporates. While there had been attempts in the past to promote telework and relocation to rural areas to promote regional revitalization, remote work will be here to stay this time for one key reason: the acknowledgement of its possibility. Covid-19 has been an unprecedented push factor in forcing corporates – especially large traditional conglomerates and manufacturers – to adopt both the necessary logistics and compliance procedures to make long-term remote work possible for their employees. While they were fully capable of going remote, there had been no incentive to push for such radical change in their work style – until the radical pandemic arrived. Fujitsu, a large Japanese conglomerate, has also taken the opportunity to speed up its remote work arrangements, with more than 80,000 of its staff working remotely, and plans to half its current office space by 20228. Even the government has been supportive of making remote work a permanent fixture, by setting aside a JPY 100bn fund from April 2021 onwards to provide individuals up to JPY 1m to relocate out of Tokyo while keeping their jobs in the capital9. With both private and public sectors seizing the opportunity presented by the pandemic to accelerate telework arrangements, it is highly likely that remote work is here to stay.

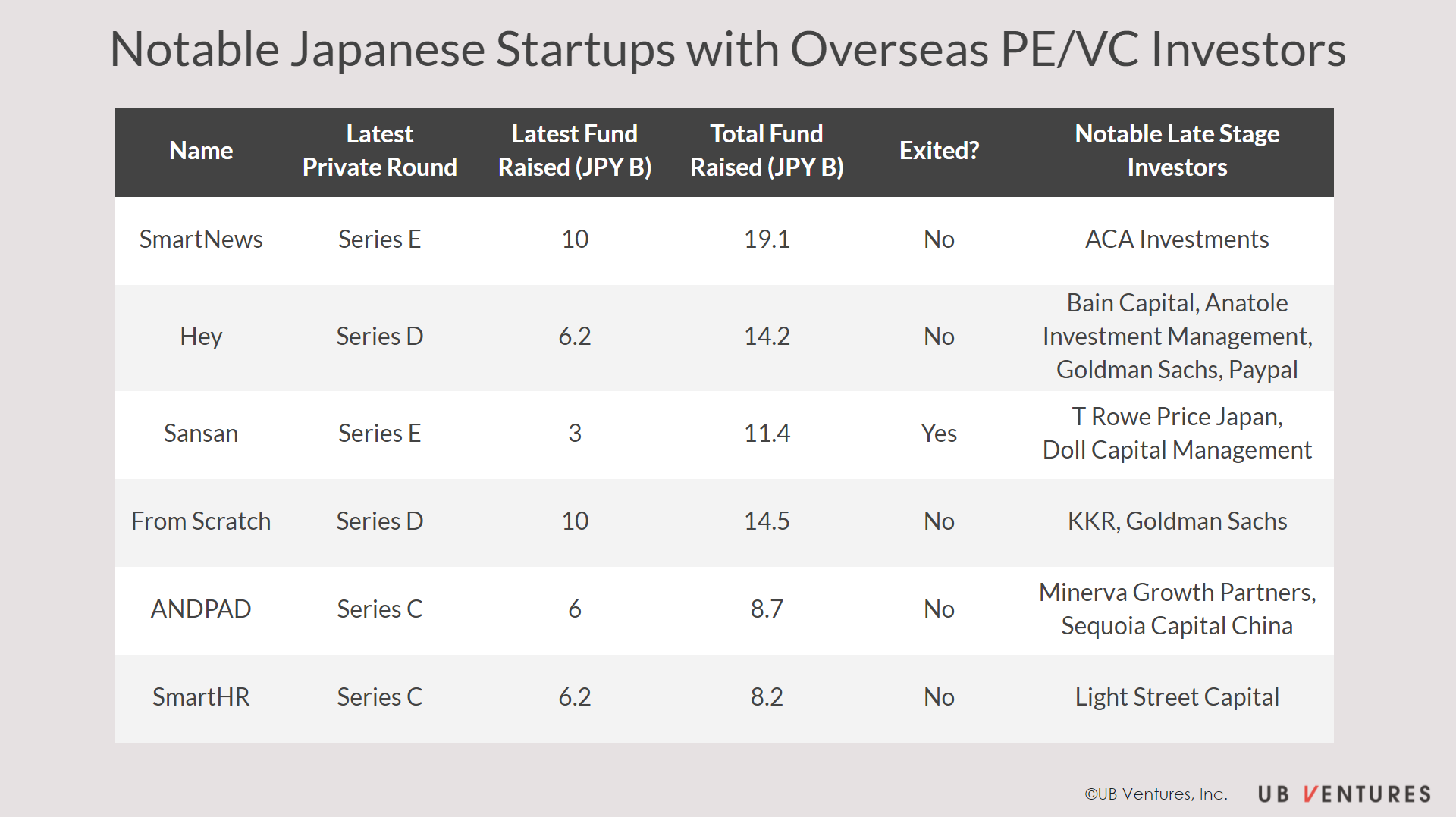

Thirdly, SaaS startups will continue to grow in number and funds raised, with larger foreign funds beginning to take interest. As capital markets mature, the infrastructure is ripening for later stage funds to take notice of the ecosystem developments – not only have we seen larger global VC firms enter the Japanese market, such as Sequoia Capital China10investing in the Series C round of ANDPAD, a Japanese real estate-related SaaS startup, but also larger multinational private equity funds injecting equity in later-stage SaaS startups as well, such as Goldman Sachs and KKR11investing into the Series D round of From Scratch, another productivity tool SaaS startup in Japan. Nonetheless, in terms of exits, there still remains the incentive to exit early via an IPO, especially with the relatively loose listing requirements on the unique Mothers Stock Exchange (where most Japanese startups seek to list), compared to the Tokyo Stock Exchange or JASDAQ. Naturally, listing would require a higher level of transparency and accountability, requiring more comprehensive audits and reporting for public investors – in many ways representing opportunity costs for giving up faster growth if they had stayed private. While the long-term trend remains that capital will be increasingly available across all stages of fundraising, the shareholders’ collective decision to stay private or exit early will be to some extent highly dependent on the direction of finance policy reforms in the future if any, but also ultimately, in the growth-driven mindset of founders themselves.

These are exciting times to be in the tech ecosystem right now in Japan. With the pandemic showing corporates and employees alike that remote work is entirely possible for prolonged periods of time, as well as with the new Suga administration on board with their aggressive efforts to speed up digital transformation across society at large, thereby increasing the supply and demand for SaaS usage and therefore SaaS startups here in Japan. While Covid-19 may have affected short-term cash-flows of some early stage startups, the sustained long-term trend of maturing capital markets means that it is likely that there will be more types of venture capital available for Japanese startups across all funding stages. On the economy as a whole, as SaaS adoption rises across enterprises, we will indeed see more people becoming interested in understanding how SaaS productivity tools can be part of everyone’s daily lives. To this end, future-ready education and exposure to new technological development is imperative. Producing quality content analyzing the major developments happening in Japan SaaS startup ecosystem right now – this is the work that we at UBV are dedicated to for the years ahead.

(*1) Fuji Chimera Research Institute, “Software Business Market Report 2019 Press Release”

(*2) Mainichi Shimbun, “Suga becomes Japan PM, forms continuity Cabinet as Abe era ends”

(*3) Mainichi Shimbun, ibid.

(*3) Bank of Japan, Outlook for Economic Activity and Prices

(*4) Japan Times, As the new administrative reform minister, Taro Kono declares war on fax machines

(*5) Initial, Startup Finance Report 2020 (note that 2020 figures are for H1 only)

(*6) Initial, ibid.

(*7) NEC, Adoption of DocuSign for document signatures

(*8) Fujitsu, Fujitsu Embarks towards ‘New Normal’, Redefining Working Styles for its Japan Offices

(*9) Nikkei Asia, Japan to offer $9,000 to remote workers in countryside

(*10) ANDPAD, ANDPAD Raises 2bn yen in Series C Extension Round

(*11) Initial, From Scratch raises JPY 10 billion from GS, KKR

By Jorel Chan | UB Ventures Associate

2020.10.22

Here at UB Ventures, we regularly deliver useful content on both Japanese and global startup trends, as well as hands-on experience from our very own venture capitalists and specialists. Please feel free to contact us via the CONTACT page if you would like to be in touch. Click here to follow UB Venture’s SNS account!

-

SCALING

METRICS

TRENDS

SaaS Annual Report 2023-2024

-

SCALING

METRICS

TRENDS

SaaS Annual Report 2022 – The Key to Industry Transformation –

-

TRENDS

Will the next Unicorn Emerge from the Industrial IoT market in Japan?

-

TRENDS

Will hanko seals ever disappear from Japan?

-

TRENDS

System Integrators – the Key to Success for SaaS in Japan

-

SCALING

Has SaaS become a recognized industry in Japan?

-

SCALING

A list of “Don’ts” when building SaaS: Lessons learnt from engaging with 200 startups

-

SCALING

METRICS

TRENDS

SaaS Annual Report 2021

-

SCALING

TRENDS

3 Successful Strategies of Top Logistics Startups in SEA

-

TRENDS

SEA-Specific Vertical SaaS

-

TRENDS

Latest SaaS Trends in SEA

-

TRENDS

The State of Vertical SaaS in Japan